The Transnational Revolution: Collective Action & Global Supply Chains

By Harper Edhels

October 2020

Coronavirus has thrown the fragility of global supply chains into sharp focus, casting new light on the implications of a sustained relationship of dependency between developing and developed regions.

In the garment industry for example, The Sustainable Textile of Asian Region (STAR) network (representing unions from six Asian states) was prompted to issue a plea to brands and retailers to consider the impact of their order cancellations and honour their contracts with suppliers due to the devastating effects on workers and small businesses in the supply chain. But with regards the multinational companies at the root of these supply chains, power of such magnitude must carry with it some opportunity.

Multinationals occupy a space that floats above the international system, transcending national structures. With the wave of deregulation that swept the capitalist system in the late 20th century came a breakdown in the ability of national governments to regulate production in their own territories, and where multinationals span multiple jurisdictions and become transnational there exists no body to call them to account. As Robert Reich, Clinton’s Secretary of Labour said in 1991: ‘the emerging American company knows no national boundaries, feels no geographical constraint.’

Up until very recently multinationals have been able to flex their muscles unchecked. The forces of capitalism naturally drive businesses into a race to the bottom, where responsibility for the negative externalities of unrestrained production has been shunned in favour of lower costs and higher profits. International institutions like the UN have shown shortfalls in their ability to harmonise responses to the globalised capitalist system, with states polarised in opinion on the extent to which social and environmental regulation should be imposed. This has allowed businesses to forge ahead with exponential production and consumption of resources at a huge environmental and social cost, with the fashion industry alone estimated to contribute to around 10% of all carbon emissions globally.

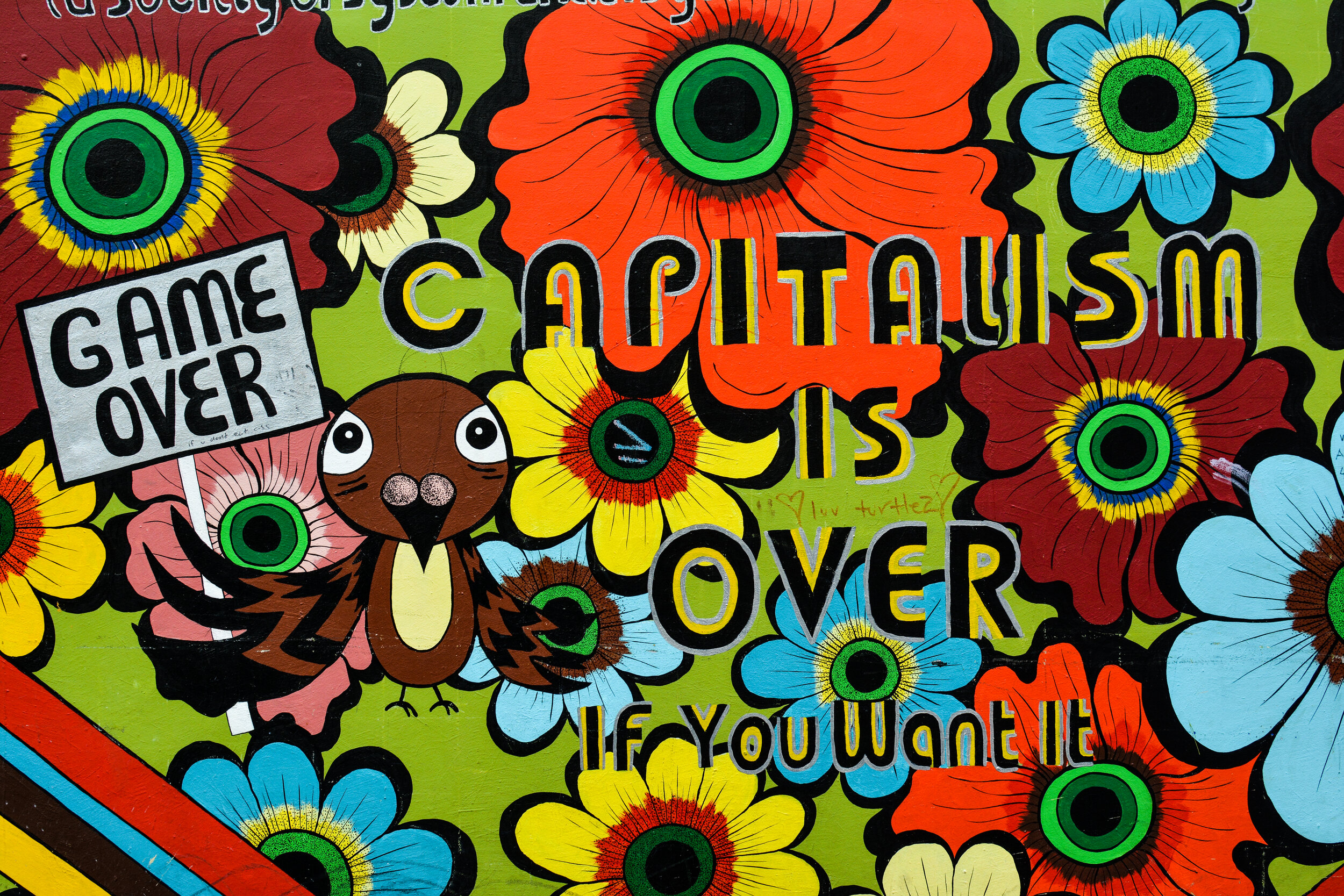

In the absence of a transnational government with the power to police and hold entities to account, the question becomes whose responsibility it is to bring about global change when we wish to see it. Consider this a call to action.

In the late 20th century, another transnational power came onto the scene: the new social movement. As a result of rapid technological advancement and increased accessibility to knowledge, new social movements facilitate collective action that is able to bypass the state. Through activism and participatory democratic action that spans the globe by uniting diverse individuals through online networks, social movements have simultaneously become transnational. Such movements solidify themselves as NGOs and civil society organisations: collections of individuals coming together to address issues across borders in support of a common public good.

The concept of corporate social responsibility has gained considerable attention in this realm. Triple bottom line strategies that incorporate not only financial considerations but social and environmental ones have become widely accepted as the strategic benchmark. Without public pressure to address negative externalities, business owners have little motivation to take the initiative to do so. In order to bring them to account, an increasing number of NGOs are laying pressure on companies to be more responsible in their social and environmental affairs.

Fashion Revolution, for example, emerged in 2013 as a desperate response to the Rana Plaza tragedy, a garment factory collapse in Dhaka, Bangladesh in which over 1,000 people were killed and exemplified the lack of safeguards protecting workers in the industry. Each year Fashion Revolution calls on fashion brands to be more transparent about where their clothes are made with the vision of reforming the fashion industry and bringing an end to human and environmental exploitation.

Civil society organisations like the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) have taken a different tack by proffering an answer themselves: a focus on remediation rather than transparency. SOMO provide tools and resources for individuals and organisations that seek remedy for human rights abuses at the hands of multinational corporations, offering a non-judicial grievance mechanism to file a complaint. Such a mechanism places the onus on the multinational to avoid the bad press that comes with being the centre of an NGO’s campaign.

The democratisation of information that comes with transparency and technology divests power from the business to the hands of the people. By reducing the asymmetry between knowledge over which a business is able to maintain a monopoly and knowledge the public can access about its supply chain, the playing field is somewhat levelled - we thus have more opportunity as individuals to drive businesses to more sustainable practices through the channels of international NGOs and mass activism.

Businesses sitting above the international system have the power and the resources to drive change, but they do not have the impetus. We, the popular movement, must be the catalyst that calls for reform.

References:

https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=2380

https://www.unece.org/info/media/presscurrent-press-h/forestry-and-timber/2018/un-alliance-aims-to-put-fashion-on-path-to-sustainability/doc.html https://ssir.org/articles/entry/sustainability_a_new_path_to_corporate_and_ngo_collaborations# https://www.fashionrevolution.org/

https://www.somo.nl/hrgm/

© 2020 Climate Just Collective